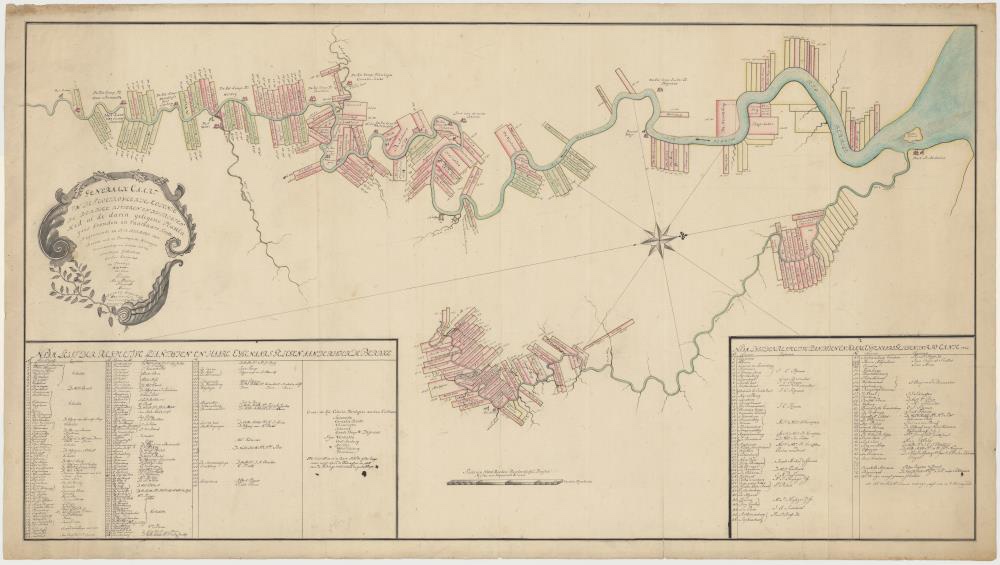

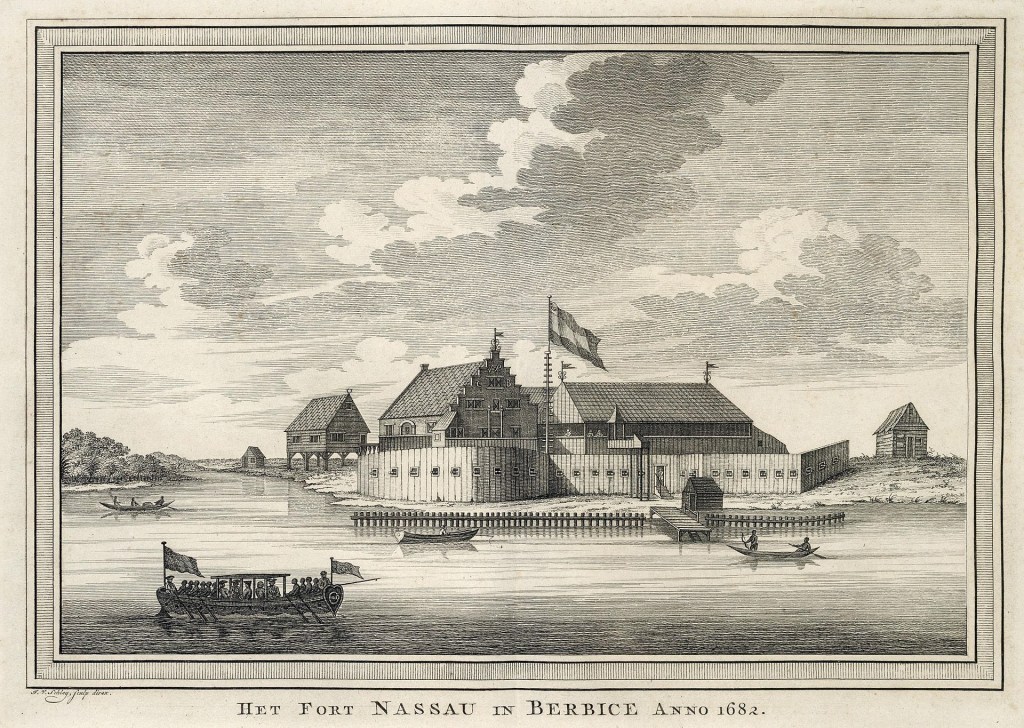

A compact of leading families ransomed the colony back from the French in 1714 and acquired possession from the Van Peele family that previously held the fief. In 1720, the families combined their holdings into the public stock-holding company of the Society of Berbice. Berbice had no major port cities or even large towns to speak of. Major tidal flows made farming along the first 50 miles or so impossible along the river, due to the enormous amount of engineering it would take to hold the salt water back. The main stronghold of the colony was the village of Nieuw Amsterdam (1627), centered around the fortifications of Fort Nassau. Here at least provided a protected wide anchorage under the fort’s meager defensives.

The colony stretched another 50 miles up the Berbice and some major tributaries. Being a tidal river, one could only move up on the almost miniature tsunami like wave that surged twice a day. Being at the equator, the tide moved up an hour each day and the traveler could be forced to journey during the middle of the night. Tent covered oar boats were used to navigate slaves and supplies to the downriver locations. The colony produced monolithic market crops like sugar and coffee, but this left little labor or time to grow basic foodstuffs. Bombas or slave drivers, organized communal gardens or hunting/fishing trips, but even these usually were supplemented with imported food items.

By 1762, the crucial shipping link had been disrupted due to war and plantations at the very edge of the colony had begun to starve. Widespread fever had decimated the small European population as well as both Indian and African slaves. With the reduced labor pool, oversight was increased. The Dutch were desperate to increase profits margins and refusing to allow any extra hands to attend to gardens or foraging, the conditions of enslavement became unbearable on the southern reaches of the Berbice.

By July of 1762, a small group of less than 50 men and women broke out of the second to last plantation on the river. They attacked the last European trading post, after skipping past the final Dutch Plantation. The trading post contained but one Dutch official, but had plenty of weapons within. Scrapping together around fourteen soldiers and a handful of Natives, this small military force confronted the rebels. The small slave band was able to lure the Europeans into a trap and defeat them. Now the Dutch employed creole slaves and swivel-gun mounted boats, with several local planters supplementing the expedition. The small rebel group broke out further south, but was forced into the jungle by the Dutch. The wet season then flooded the forest and eliminated access to food, soon cannibalism started and conflict led to murder.

After three rebel children were killed, the group split in an attempted breakout. The smaller groups were hunted by native allies of the Dutch and the rebel leader was murdered by the parents of the children killed. The trials and tribulations of this minor rebellion would foreshadow 1763. “What the slaves have failed to accomplish, others would soon carry out.” This was the ominous warning given by a slave set to be broken and crucified for his involvement in the 1762 rebellion.

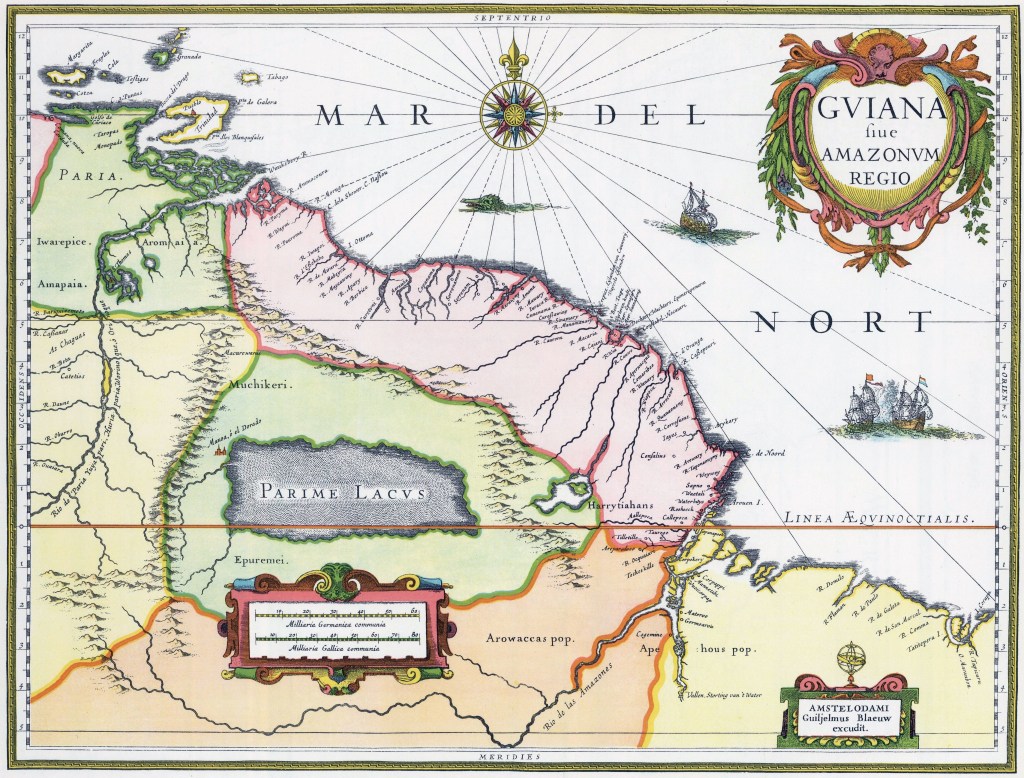

By 1762, the Seven Years War had wrought terrible hardships upon the small peripheral Dutch Colony of Berbice, on the northern coast of South America. Berbice encompassed much of the modern day territory of Guyana and was linked to its sister colonies of Suriname and Demerara. No more than 400 Europeans occupied a colony, accessible only by tropical rivers and creeks for hundreds of miles inland. Marked by a dry season and an impassable wet one, the colony eked out a profitable existence through the labors of 4,000 enslaved Africans.

Directly abutting the Berbice River and several important tributaries, Plantations were laid in long rectangular plots connected by a watery highway to the coast. Surrounding the colony were open savannah, dense tropical jungles, and rough mountain terrain. If a slave could someone escape the connected plantation system, the Native Amerindian population lay in wait. Years of deals and negotiations had lead to an alliance between the Dutch and Native peoples. Native populations would police the borders of the colony and return enslaved runaways, for manufactured goods/food stuffs. They would also provide guides to seek out small maroon groups in an attempt to head-off a much larger issue that had arose in the neighboring colony of Suriname. Native forces would be free from molestation and enslavement (Some Enslaved Natives did exist), if they helped Dutch forces keep the plantation society in order.

Above the Native peoples and the African born slaves, sat the creolized African overseers. Being a tiny and out of the way colony, most slave ships skipped over Berbice. Slave labor replacement was sought through natural birth and those who led extended multi-plantation wide kinsfolk groups, were tapped to head the daily operations. Ironically it would be a chance encounter with a slave ship that would light the fuse throughout the colony. Berbice wasn’t always a quasi-national endeavor for the Dutch, but instead was founded as a personally held fief in 1627.

West African world cultural practices viewed such human deprivation like starvation as caused by evil and required corrective social action. Berbice had not experienced widespread maroonship or particularly cruel oversight before the Seven Years War, but conditions changed.

An inquiry into the root of the 1762 revolt failed to find any large scale conspiracy, but neither did it identify a clear cause. Any remaining rebels were whipped and sent to the fields, but the small revolt had demonstrated the weakness of Dutch power to starving slaves. In February of 1763, slaves on the tributary creek Canje, rebelled and made for the border with Suriname. Dutch forces and Native troops managed to contain them along the Courtyne River which marked the border. As soon as this rebellion seemed over, a major revolt took place on four centrally located plantations south of Fort Nassau and in the heart of the colony.

Several white overseers were decapitated and their heads placed on spikes along the river. Most remaining Europeans made their way to Plantation Peereboom south of the conflagration. The rebels now had free reign to seize control and resupply themselves in the productive heart of Berbice plantation territory. They now had a choice between targeting the gathering of Europeans with their native slaves and loyal Bombas to the south or attacking Fort Nassau to the north, only eighteen soldiers stood guard over a crumbling fortifications. The merchant ships sheltering by the fort were commandeered by panicked Europeans, who then refused to sail upriver to help trapped Dutch colonists.

Meanwhile Peereboom was quickly becoming the central strongpoint for all trapped Colonists and their dependents. Some 70 Europeans accompanied by loyal enslaved Africans and Natives had filtered into the plantation. A wall was built around the central house and a field of fire was established by tearing down out buildings. Letters were sent to Fort Nassau, but the governor could only make vague promises. Over four hundred rebel slaves attacked the fortified plantation with red hot nails attached to arrows, used to set the buildings ablaze. Dutch forces held off repeated attacks, but Europeans were cut off from water. Talks allowed Europeans to give up their position and flee by boat upriver.

As the group of Europeans filed down the hill toward the boats, the rebels attacked the vulnerable column. Certain Dutch men were singled out for horrendous torture and most were linked to the harsh punishments early meted out to the prior rebellion the year before. Men were flayed, quartered and beheaded, but first made to watch their wives/daughters being raped then bludgeoned. Company managers and physicians were also targeted for harsh punishment and murder. Surgeons experimented on slaves and the managers had sought to wring out any remaining profits despite starvation. A full third of the Europeans refugees were killed and the rest were captured.

The destruction of Peereboom extinguished Dutch power on the upper Berbice and allowed the rebels time to slowly march north by consolidating abandoned plantations under their rule. The rebel target would of course be New Amsterdam and Fort Nassau. Fort Nassau was abandoned and the remaining several hundred colonists moved down river toward the coast, as Rebels marked downriver toward the final major Dutch plantation on Berbice. While it seemed that some minor plantations to the north were continuing to operate, remaining Europeans and their wares arrived at Fort Saint Andries near the coast, which was surrounded by savannah.

The tiny small outpost quickly became a refugee camp, while colonists clamored to be allowed to take the remaining ships home. Groups broke into local plantations for food and received pleas from Bombas who were still loyal to the Dutch. Many plantation slaves have stayed neutral and were being abused by rebel bands. They would help the Dutch reestablish a foothold in some plantations up river, if they arrived with military aid. All Dutch control over the Berbice River had been lost, so the colonists clustered on the coast asked for aid from Suriname.

Over one hundred soldiers and food were sent from the colony, with some forces being assigned to patrol the river, that formed the border between the two colonies. Using the remaining ships and newly arrived soldiers from Suriname, the Dutch counter-attacked Dageraad Plantation on March 28th, 1763. This was the largest plantation on the lowest reaches of the Berbice and a perfect location from which to launch a reconquest of the colony. Rebels had withdrawn to the woods before the European arrival and observed their movement. Tipped off by the loyal Bomba, Europeans forces were prepared for an assault by over four hundred Africans the next day. The Dutch force of over ninety soldiers was able to repel the rebel advance, with only a single casualty. Rebel forces astonished the Europeans with their organized and coordinated tactics, with the possible use of archers and flag bearers. Theee men to a musket ensured constant fire and removal of wounded rebel fighters. Many of these tactics arrived with war captives the year before in a chance visitation of a slave ship from Africa.

Many male slaves were captives taken in war from sophisticated and militarized kingdoms, where they likely honed specialized skills. Religious spells and honorifics also mirrored West African cultural practices as well. Coffey the leader of this rebellion, was brought from the area of what is now Ghana as a child. He was of a high ranking family and rose quickly to be a major leader on his plantation. Accra was 2nd in command and came from a similar noble background. Though defeated on the very lower stretches of the Berbice, the vanquished rebel forces had only been but a minor part of the overall slave army. Several thousands rebels and their dependents still ruled 3/4 of the colony and could supply themselves from the seized plantations.

To help stabilize the situation, the Dutch called upon the Carib natives of the Orinoco River, with promises of bounties paid for every rebel hand brought in. To forestall for time, the Dutch engaged in a series of written correspondence with the rebel leader Coffey. Coffey revealed his 2nd in command had attacked the Dutch without his approval. He offered to split the colony in two with the slave army controlling the upper reaches of the Berbice and the Dutch continuing their plantation society upon the lower courses. He asked for free trade to the Ocean and requisite foodstuffs to start his new nation off. While the Europeans received support from neighboring colonies and the Island of Barbados, the rebels sought to recruit many of the neutral slaves that had recently self-emancipated after their white managers fled.

Force was used to convince recalcitrant Africans to join. Rebels sought out the various creeks and tributaries thought to be hiding places and assigned flying columns to carry out this task. Training was opened up on several central locations on the middle course of the Berbice and raw recruits were schooled in the art of soldiery or as tradesmen. Protected talks took place through May of 1763, but the Dutch had received further naval support from the Caribbean. While their artillery advantage was evident, the Dutch reinforcements began to sicken with Yellow Fever. Angry foot soldiers had begun to grow tired of the talks and the Rebellion’s second in command could no longer hold back his men. On May 18th, over six hundred rebel soldiers surrounded and attacked the Dutch stronghold, on a large Plantation commanding the lower course of the Berbice. While putting extreme pressure on the hundred or so European defenders, the rebel forces could not break through, due to the Dutch Naval cannon fire from the River. The rebels were caught mid-river as they retreated in their canoes and sustained heavy losses, only a slack tide prevented a complete rout.

European firepower was soon offset by mutiny a month later. Much of the “Dutch” troops sent were actual foreign mercenaries who were past their contract date. A huge issue for the hired men was the manual labor that was required of them in lieu of the enslaved or Natives. Dutch authorities were under strict orders to not place any further undue burdens upon the Native peoples needed to transform the colony into an open-air prison. So on July 3rd, the soldiers mutinied and tied up their officers. The largest grievance expressed was that over plunder. The foreign troops felt that the Dutch officers actions in confiscating plunder to be redistributed by the company, were in fact a ruse to cheat them of value. Most of the rebel Europeans attempted to reach the Spanish on the Orinoco River several hundred miles away. Dutch authorities authorized native allies to use force in recapture, but a decision was made to throw their lot in with the slave rebellion.

This regional slave commander was informed that these Europeans were part of the recent successful expeditions and had many executed on the spot. When Coffey heard of the news from his headquarters at Fort Nassau, he secured the remaining Europeans and had a regional rebel executed for his actions. The rebellion had begun to show a divide between the Berbice and Canje creek factions nearer the Suriname border. Prisoners were now sent to the Dutch headquarters on the lower courses of Berbice for further talks. Suddenly the talks ended and the Dutch received word that Coffey had committed suicide. His second in command was enslaved and a coup had occurred within the ranks of the slave army. A council had condemned Coffey and his suicide paved the way for new leadership.

Several European child were ritualistically murdered to accompany him as servants in the afterlife, according to West African tradition. The stalemate continued into the August, as the dry season commenced. The Dutch turned all eyes to the sea, in a vain hope that help might arrive any day. The Dutch government had by mid-summer received the news of the extent of the uprising and decided a military intervention was necessary.

Three Naval ships and 1,100 soldiers set sail by the start of August. Four additional frigates and hundreds of more mercenaries were also organized and sent by November. The European forces that arrived first, set about eliminating rebels from the lower creeks off the Berbice. Now Dutch reach could extend down the Berbice from the coast and they could push toward Fort Nassau. The rebellion had fractured and fled upstream.

The recently arrived former Ghanaian warriors on the slave ship the year before, had firmly taken control of the rebellion from the Creole former leaders. They had gone on to enslave the creoles and drove away a faction of rival Angolan peoples into the bush. One of the main wedge issues had apparently been the orders to restart plantations and enforce field labor. The revolving coups within rebel leadership could be seen as a competition to force others into this submissive position.

By late November, the Dutch were ready to launch a four hundred man expedition protected by several frigates, downstream after the retreating rebels. European forces had also been sent to the borders of Suriname and Demerara to prevent any slave retreat. Native allied forces were outfitted in Suriname to flush any rebels out in hard jungle fighting. The Dutch authorities intended to round up as many neutral and dissatisfied former rebel slaves as they could, due to their lack of manual labor needed for the expedition, but Dutch Naval advances caused the rebels to disappear into the woods. The last plantation on the Berbice River became a major staging ground for the formerly enslaved. Fifty Europeans and around two hundred Natives surprised them by coming from north via the colony of Demerara. More than fifty rebels were killed and fifty more former rebels taken captive. This plantation had been a supply camp that secured the rear and now rebels further up the Berbice were caught in a trap.

The Dutch Naval squad closed in and cornered a major rebel force. Given the conditions, rebels forces melted into the creeks and surrounding jungle. While now controlling most of the Berbice, small bands of slave fighters continued to harass Dutch forces by February of 1764. Harsh jungle conditions caused a flow of starving enslaved peoples to return to Dutch lines and these former rebels were employed to gather refugees in the forest. Hundreds were brought back to Dutch lines and valuable scouting information on the dwindling rebel bands was gained.

On March 22, 1764, Dutch forces led by a band of turned former slave rebels, set out in search of the coup leader. Led by the rebel guides, the last of the rebellion leaders was caught by surprise in the swamps near the border with Demerara. By April, the last of the rebels were being ferreted out. Several hundred slaves were questioned in a judicial investigation, with one hundred and twenty men and four women ordered to be executed. Hanging, the rack, the wheel, and burning at the stake were all punished that were handed down. On April 28th, most of the main leaders were hung, with several broken on the wheel or slowly burned alive. Still a powerful exchange of accusatory terror being cast by the condemned toward a particularly cruel plantation owner, silenced the entire proceeding. The Governor stepped in to rebuke the plantation owner, in a tiny show of respect for the truth be spoken by the dying man being broken upon the rack.