The infamous “Code Noir” was not known by that term until almost 40 years later. Proclaimed by Louis XIV in 1685, the collection of Slave codes was originally referred to as “The Edict of March 1685.” It slowly morphed into the Ordinances and finally the short hand term of “Black Codes” by 1720 in the French Antilles. Historian Brett Rushforth writes “The law grew out of a series of power struggles between the enslaved and their would be masters. These struggles, first registered in local acts designed To solve immediate human problems, expressed masters and slaves opposing interpretations is slavery and competing aspirations for life in the colonies. They this reveal not only the ideals of French Masters, but also the actions of enslaved Africans and Indians whose daily assertions of their own humanity challenged the fiction of their status as property.”

The majority of Slavery in New France usually concerned the trade is native war captives from the Great Plains through the pays d’en haut. The small geographic size of the population and relative isolation of new France, forced the new habitants into an already established system of native economic exchange. Native war captives were an essential part of this pre-existing system and one the newly arrived French were loath to interrupt. Accepting cultural practices and value systems allowed the French to not only maintain their tiny presence amongst a sea of natives, it enriched their connections to the familial and political networks needed for free transit in pursuit of the fur trade.

“ By accepting a little flesh to stabilize their alliance with western Indians, the colonists of new France acknowledge the symbolic power of captive exchanges to build a union and foster peace. Yet, rather than willingly embracing their allies’ captive customs, French officials assented only when natives demanded their participation. Ironically Indian slavery originated as a partial defeat of New France’s power over the Native inhabitants. the French built an an exploitative labor system that redirected their impulse for control and domination onto distant Indian nations,” wrote Historian Brett Rushforth. Plains Natives were enslaved through French allied tribal raids and either gifted or traded to them through their string of outposts throughout the Pays d’un haut. Most served domestic roles helping to care for large Canadien families in Montreal or Quebec, while others helped facilitate the vast fur trading enterprises that kept the colony afloat.

The French Caribbean’s center of gravity was shifting by the middle of the 18th century with Saint -Domingue rising to prominence. The vast majority of African slave imports now moved toward this colony and left the southern French Antilles under supplied with enslaved labor. A 1739 Royal ban on Indian enslavement made the crisis even worst in islands like Martinique, whose plantations contained numerous natives captured in raids to the south in places like the Grenadines or the northern coasts of South America. The French King had sought to stop these raids against peoples the state was not in conflict with. New France’s population of Native slaves were captured in battle against nations hostile to French interests. How would the Crown view the transportation and sale of Canadian natives in the Caribbean?

In 1742, a French sea captain arrived in Saint Pierre on the island of Martinique. His cargo included a teenage native slave girl from the Great Plains. Native slaves were fetching four times the purchase price on islands like Martinique due to the diversion of slave ships to Saint-Domingue. The French sea captain found a ready buyer who was a wholesale merchant. The Captain was promised payment upon resale of this Native Slave girl. The Native teen was apparently told of the recent Royal decree banning Indian Slavery and she ran away before she could be resold. The French captain sought to be reimbursed for the loss of his property. His case was at first rejected by local authorities on the island, as they applied the recent decree to mean the Native girl was indeed free. The ruling was appealed and the King intervened to state that the former decree did not apply to Canadian Native Slaves captured in battle against known enemies of France.

The ruling opened up a little known trade that operated in a legal gray area between New France and the French Antilles. Native captives became more prominent in cargo listed and attempts to set up a formal trade were started. This failed mainly due to the racial structures needed to organize African based slavery in the French Caribbean versus the tactic diplomatic and familial networks the connecting the society of New France. Authorities in Canada could not apply the strict racial categories and separations to Native interactions, otherwise they would risk losing their entire enterprise. POW status became the defining markers of enslavement and a small trade of Natives continued to trickle south until the fall of Quebec.

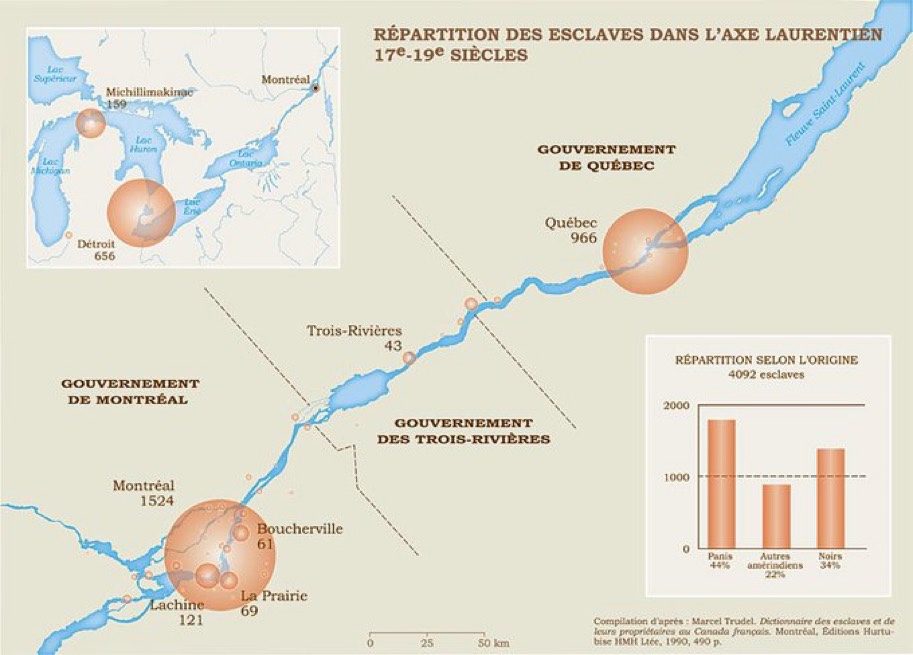

African Slavery made up less than 10% of the total enslaved, but were concentrated in the Saint Lawrence River Valley. Several hundred African Slaves were used in a mostly domestic manner in urban centers like Montreal. African slaves came to the Saint Lawrence River Valley indirectly as part of French “Prizes of War” taken from English ships or settlements in the Caribbean. Other slaves were brought over to the colony in small numbers as they accompanied their owners. No direct slave importation is recorded to have arrived in Quebec, but French authorities had to categorize the rising numbers of Africans by the middle of the 18th century. All Africans in New France were categorized as “Slaves” to distinguish them for Native “POW” captives that could still obtain their freedom. Individuality was removed and African captives now were only considered to be property. African Slavery constituted between 5-10% of the entire Slave population of New France with Montreal being the epicenter of African Slavery in Quebec. It’s here where we can glimpse some acts of agency.

Historian Allan Greer recounts a story of Marie-Joseph-Angelique who set her mistress’s Montreal house on fire in 1734. The blaze burned forty-six buildings, but didn’t kill anyone. She attempted to flee with a white indentured servant lover, but was quickly captured. Angelique was born in Madeira and was enslaved by the Portuguese about 20 years earlier. She was bought by a Dutch Merchant and and sold in a New England port to a French Montreal Merchant. Her trail reveals the nuanced layers that encompassed African Slavery in the Saint Lawrence Valley. Testimony describes her constant outings and friendly interactions with neighbors and children. Her friendship with a native slave of the neighboring house is also highlighted. Life was tough as her bed was a pallet and she received physically beatings from her mistress. She was recorded as having three children who sadly didn’t survive infancy and it seems the father was a Madagascar born slave through which Angelique’s owners were forced to sexually assault her for possible offspring. She developed a feud with another white indentured servant and demanded the woman be fired. Astonishingly her owner compiled and had the offending servant dismissed.

Angelique’s relationship with a white male servant grew and she demanded the same path to freedom as she witnessed other Native slaves being given. Her mistress refused this request and Angelique resisted. “She talked back to her owner, threatened her with death by “roasting,” quarreled with the other servants in the house, threatened them, too, with “burning,” and made life so unbearable for her fellow servant Marie-Louise Poirier that she quit her job.” Her owner became irate and sold her to a Quebec merchant who then intended to forward her to the dreaded French Antilles. A sale to the sugar islands would mean certain death for Angelique and she attempted revenge by setting the fire before she was sold on. Her trial refused to recognize that she acted alone and attempted to break her through torture to expose any accomplices. She never broke under horrendous pain and was given the mercy of a hanging, before her body was publicly burned at the stake.