Creoles, Kalinagos, and Imperial British Border Policy in The 18th Century Caribbean.

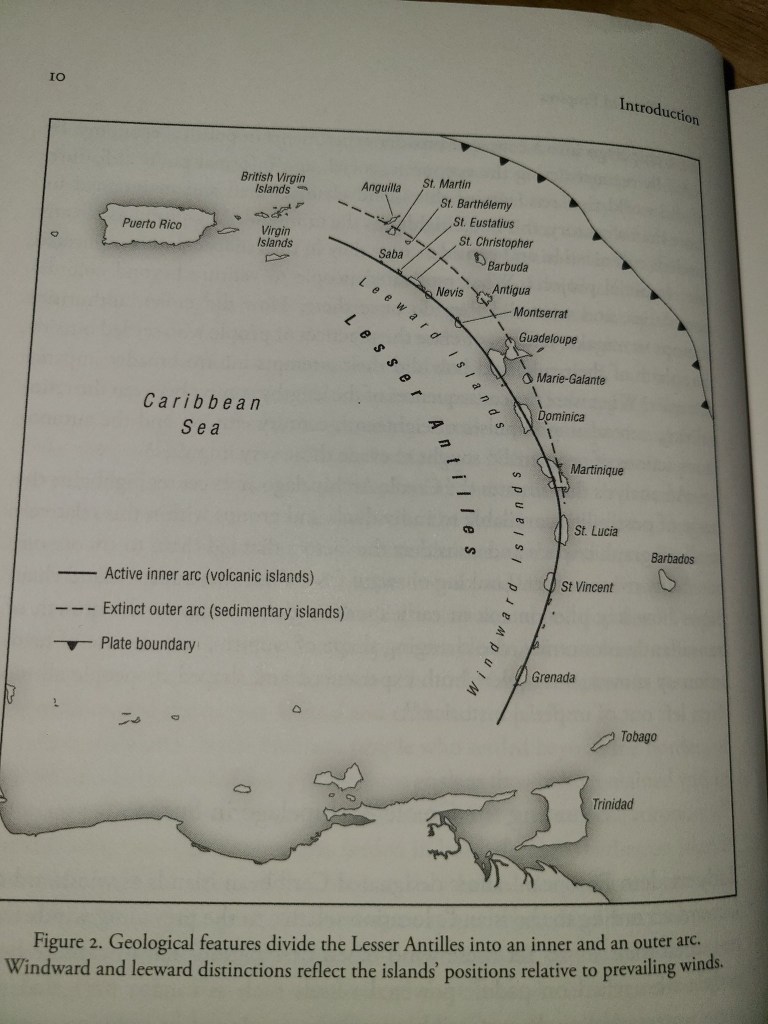

The entry point of societal recognition in the French Atlantic World was the local Parish priest. Any important documents that would allow access to or movement within this colonial sphere, would require priestly signature. Official status and legal recognition was achieved upon the document being registered into the local church archives. The Seven Years War brought rapid change to the Lesser Antilles or Windward Islands. Imperial Sovereignty switched in the blink of an eye and centralizing surveys were undertaken that saw widespread monocultural sugar production as the goal. Formerly semi-autonomous maroon and fully autonomous native zones, were now given over to goverment parceled land. Thriving communities of mixed race peoples had existed outside the formerly fluid boundaries of Imperial rule, but now they were subject to both capricious and restrictive racial definition laws.

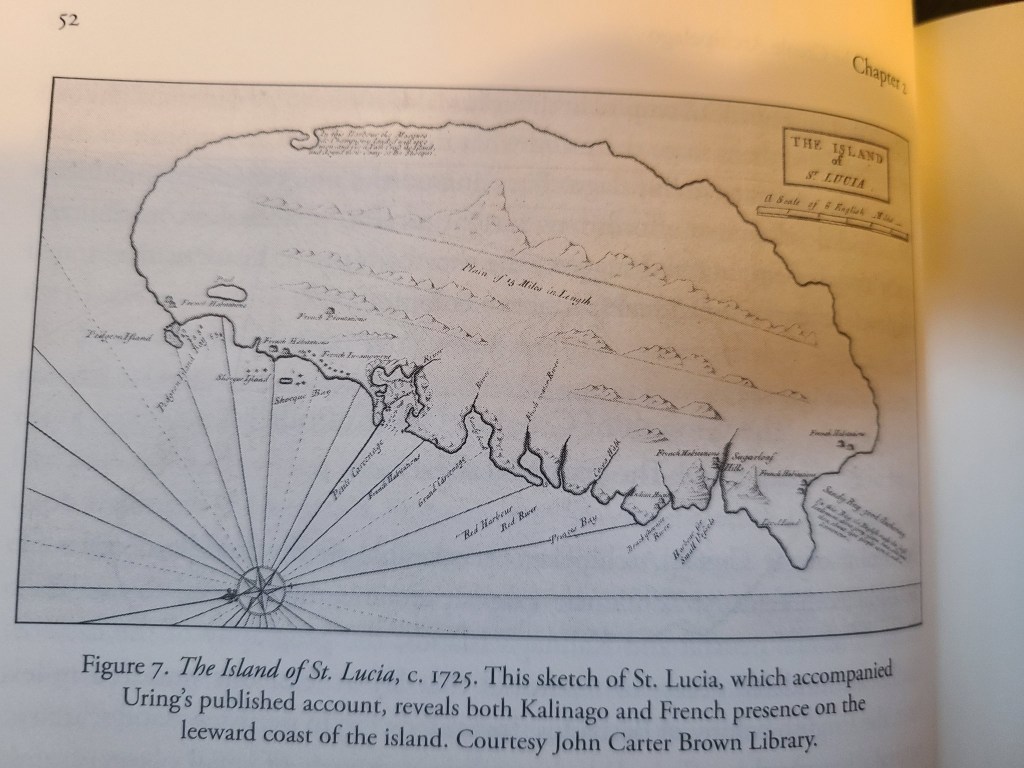

In the French Atlantic former Kalinago territory of St. Lucia, formerly free mixed race people were subjected to a stricter racial social hierarchy developed on Saint Domingue. A large and growing population of “gens de couleur” lived on the prosperous French western third of the Island of Hispanola. Close documentation requirements sought to close the “field of liberty” to free blacks, so this population was forced to endure the “psychic brutality of having to argue for one’s full humanity” according to Brett Rushford. On the eve of the American Revolution, 40,000 freed people of color lived in Haiti. As restrictive laws increased, this group sought to officially establish and document their status. By the 1780s, freed people of color made up the majority of marriages in many parishes according to Robert Taber. These racial categories became exclusively documented in the years after the 1750s and no one could escape a label on their union.

The infamous “Code Noir” was not known by that term until almost 40 years later. Proclaimed by Louis XIV in 1685, the collection of Slave codes was originally referred to as “The Edict of March 1685.” It slowly morphed into the Ordinances and finally the short hand term of “Black Codes” by 1720 in the French Antilles. Historian Brett Rushforth writes “The law grew out of a series of power struggles between the enslaved and their would be masters. These struggles, first registered in local acts designed To solve immediate human problems, expressed masters and slaves opposing interpretations is slavery and competing aspirations for life in the colonies. This reveals not only the ideals of French Masters, but also the actions of enslaved Africans and Indians whose daily assertions of their own humanity challenged the fiction of their status as property.”

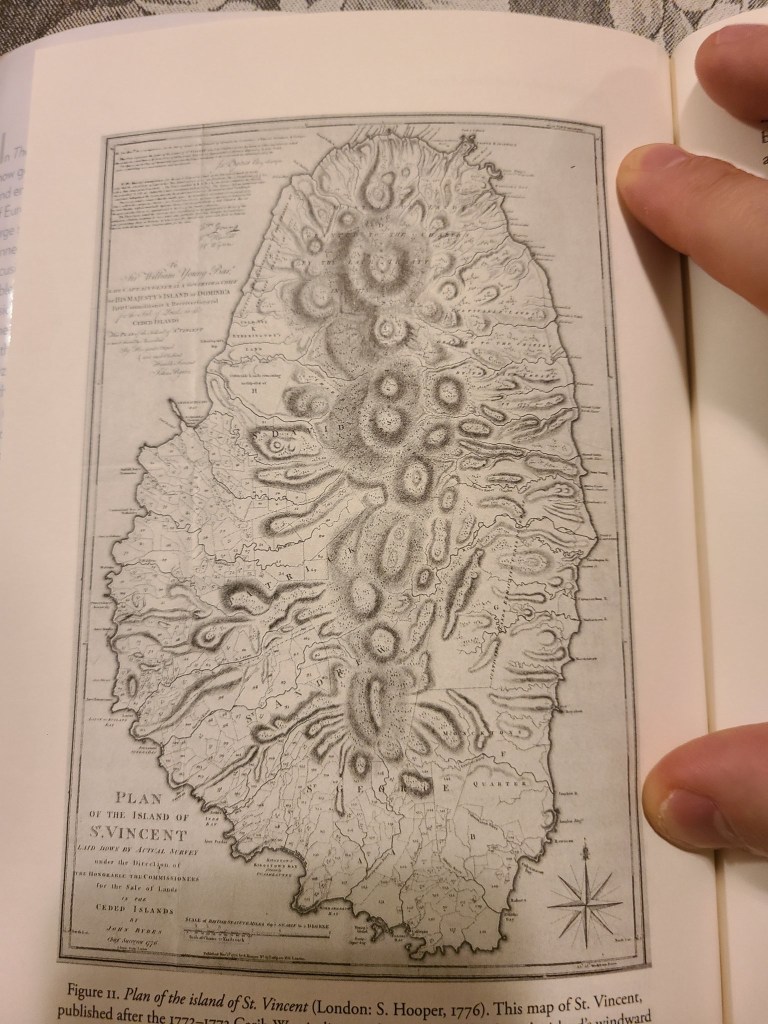

I taught a large number of Garifuna students in East Harlem, but I never realized their origins are to be found in the Caribs, a l native peoples found in the Caribbean at the time of Columbus’s arrival. As outlined in Tessa Murphy’s “The Creole Archipelago,” The eastern islands of the Lesser Antilles provided native respite and then “neutral territory” on the periphery of European colonial empires. Here developed the “Creolized” syncretic societies of Dominica, St. Lucia, Grenada, and St. Vincent. The consolidation of European imperial structure after 1763 in the Caribbean and renewed fighting due to the American Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, forced creole society to squeeze into tighter imperial frameworks. British victories in the Seven Years War had greatly expanded the physical space and cultural impact of their rule in the Southern Caribbean. They would now have to contend with a French speaking and creolized society of racially diverse peoples, eager to mark out their own boundaries. They would encounter a variety of peoples and situations, where a mix of conciliation and force would be deployed in order to stabilize British rule. The British had been seen as willing to use mass deportations in Acadia as a method to subdue unruly inhabitants and the southern Caribbean would be no different.

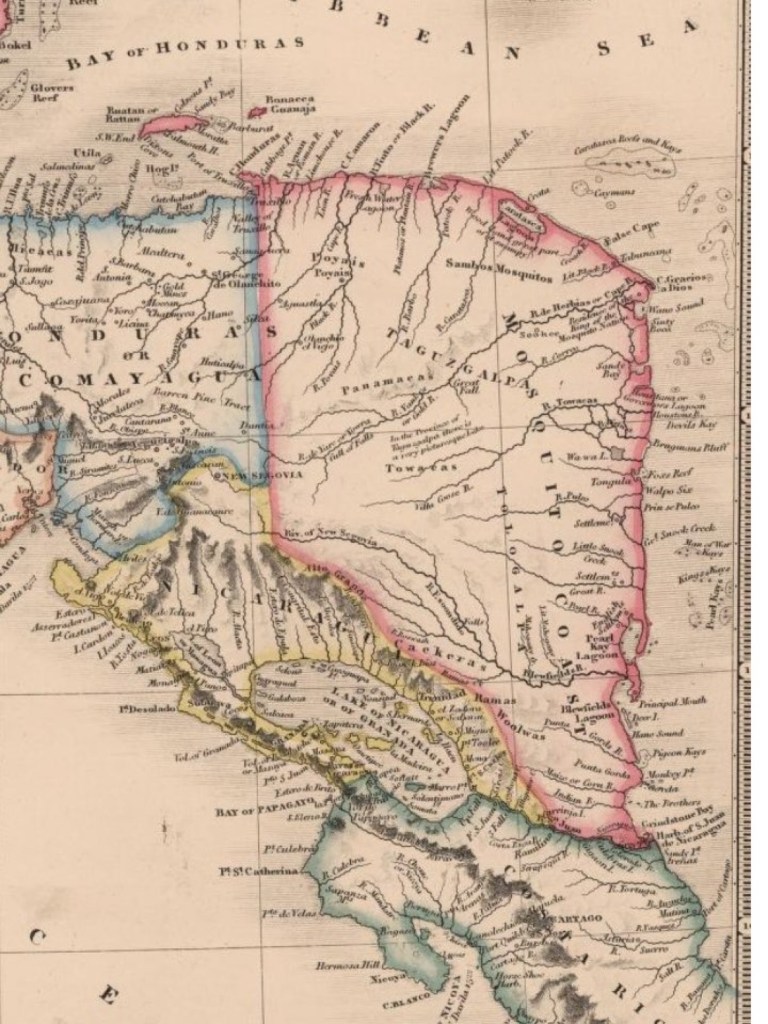

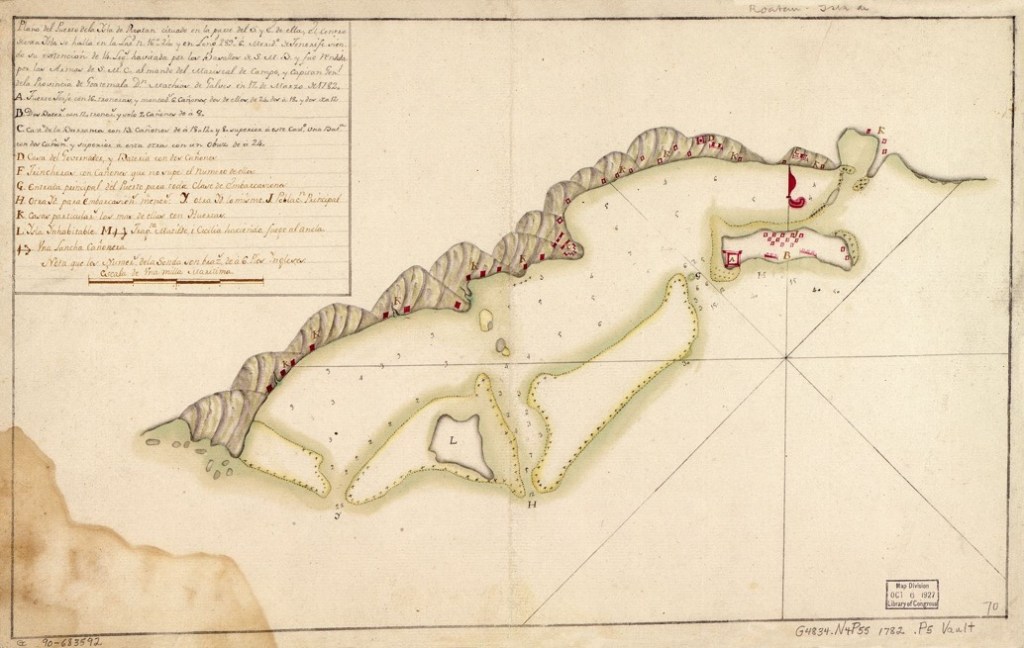

The Battle of Roatan was fought in 1782, as part of the larger American War of Independence. The Mosquito Coast of modern day Nicaragua and Honduras, was an important source of hard woods and had been unsuccessfully settled by the Spanish. Though still claimed as part of their empire, this area was in reality contested between the Spanish and British crowns. British efforts at cementing diplomatic ties with local natives, gave them the upper hand by the 2nd half of the 18th century. The Island of Roatan occupied a strategic position supporting British claims north to the Yucatán and south to Nicaragua. British woodcutters and then pirates made Port Royal their home on the island. Almost 2,000 souls occupied the site at its high point, with Port Royal defended by two fortifications called Fort Dallings and Despard. These were situated respectively at the opening mouth of the harbor.

Spanish entry into the American War of Independence gave the Crown a chance to expel the British from the coast of Central America. The Spanish first moved against the British off the coast of modern day Belize and in the Yucatán. Many of the survivors of these attacks fled south to Roatan and the protection of the forts at Port Royal. Major preparations were undertaken by the Spanish at Trujillo, which lay directly south of the island on the Honduran coast. The flow of arms and supplies to the Americans in the north, hampered the campaign until after the American victory at Yorktown in 1781.

In March of 1782, eight hundred Spanish soldiers and three frigates sailed toward Port Royal. After refusing to surrender, Spanish warships reduced the British Forts guarding the entrance to the harbor. Barely one hundred British troops made up the garrison and these were forced to flee to the hills outside of the port. The Spanish warships continue to bombard the town and defenders in the hills. British forces were had no other choice but to surrender by nightfall on March 16th, 1782. Slaves and other supplies were plundered by the Spanish and sent along with the POWs to Havana. The Spanish would go on to sweep the British from the Nicaraguan coast as well, but these British losses would be quickly reversed after Battle of Les Saintes. Spanish gains on the Central American coast, Roatan and The Bahamas would be reversed.

In 1795 the British removed 5,000 inhabitants of St. Vincent and sent them to the island of Roatan. This remanant population of mixed African and native peoples became known as the Garifuna. Their descendents spread out along the Central American Caribbean coastline and helped the British to both resupply their shipping and harvest hardwood.