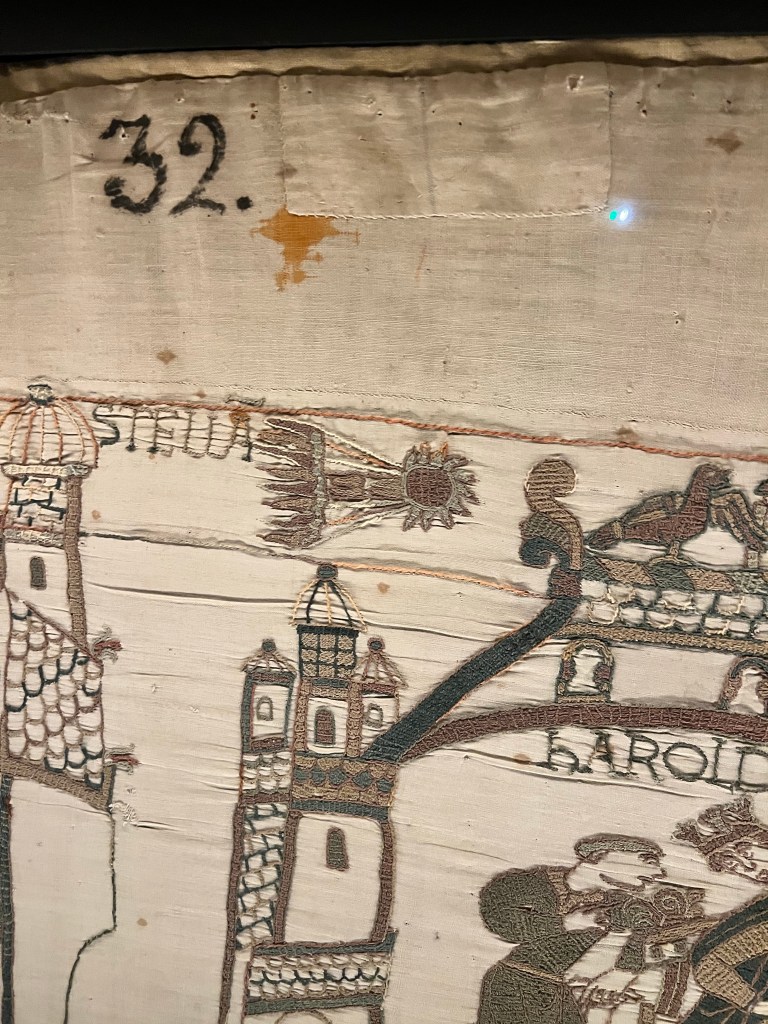

The Tapestry is both completely shrouded in mystery, while simultaneously being a world famous source for one of the key turning points in western civilization. Our first mention of it was in a 1476 inventory of the Bayeux Cathedral, where it was being displayed for eight days each November until 1728. It was almost destroyed in the French Revolution and the Nazis highly contemplated taking the work with them.

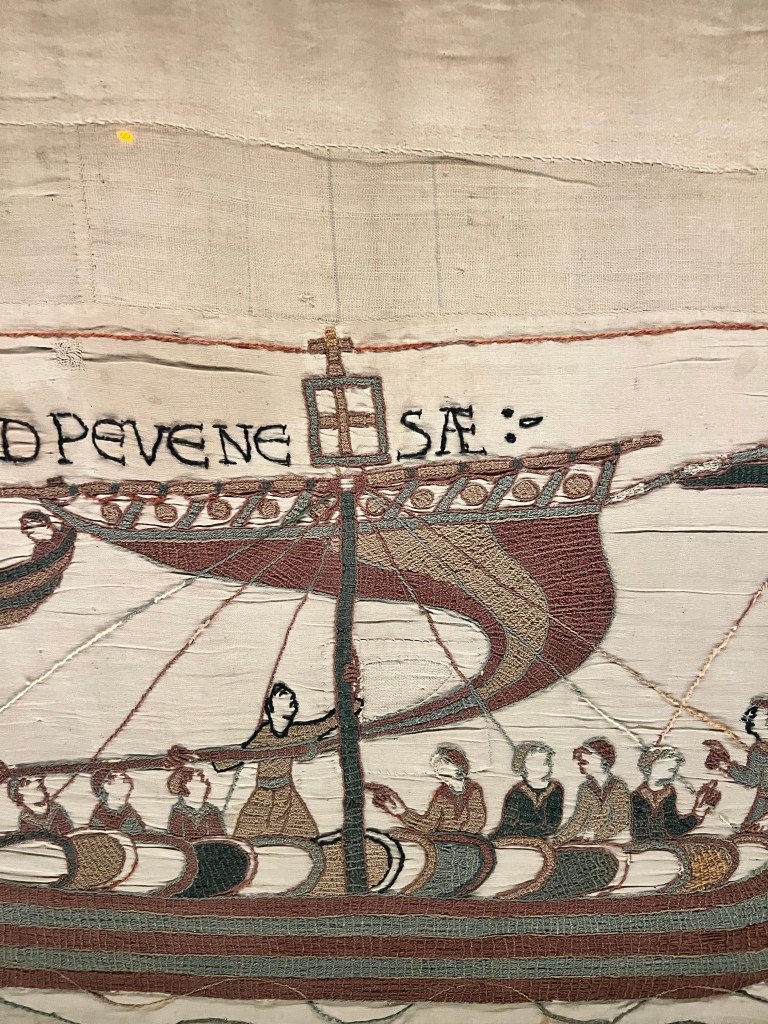

At 223 feet long and still missing several ending scenes, the Tapestry is the largest of its kind that has survived intact to the present day. We think it was produced in England and arrived in Bayeux before the end of William’s reign. The direct link is Bishop Odo, who was William’s half-brother and whose episcopal seat was Bayeux Cathedral. The patterns and style closely match other works produced at Canterbury Cathedral. Though shortened today, the Tapestry would have perfectly fit into the nave of the newly constructed Bayeux Cathedral behind the altar. Bishop Odo commissioned the work because of his central inclusion in the narrative versus the other historical source materials.

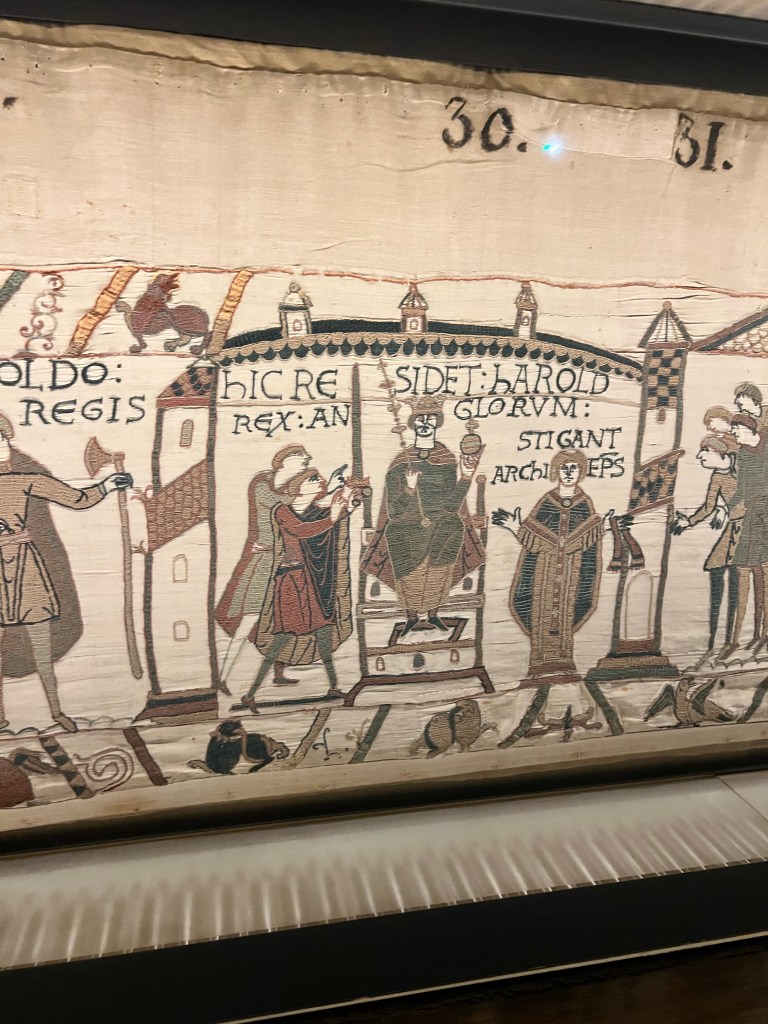

The tapestry contains an interesting detail on the oath Harold swore to William, it depicts the location as being in Bayeux. This is the only historical source to claim this. Odo is also depicted in the ranks of the Norman knights at the Battle of Hastings, along with the names of his retainers. The narrative is definitely one of Norman hindsight, but it also contains some tidbits of English sympathy for the fallen Harold. Harold is depicted as saving William’s life and contributing to his campaigns in Brittany during the time after his parole from William’s vassal. Harold’s legitimate succession from Edward is depicted with the dying king reaching out and touching Harold in front of his courtiers. The tapestry is designed with interpretation in mind and the neutral ambiguity of a courtier. Even the “Oath” that Harold swears is depicted ambiguously, the text over that accompanying scene on the tapestry doesn’t specify what was contained in the “oath,” just that it was performed.

The death of Harold Godwin is depicted with the traditional “arrow in the eye,” but our sources are mixed. Many early sources from the time backup the Tapestry depiction, but the we do have later sources stating Harold was cut down in an Norman Calvary charge. The famous death scene does contain two men under the text, but both figures are quite different in dress and armament. Only one man has an arrow protruding from his eye and we can comfortably identify this figure as Harold.

The role of William’s half siblings is also communicated to us by their inclusion and Odo’s role in the invasion. The Conqueror’s extended family provided the hundreds of ships needed to pull off such an daring feat. Odo would rise to become the second wealthiest man in England and Earl of Kent after the conquest. He served William until 1082, when he was deposed for using military resources to pursue the Papal throne. Odo was thrown in prison for five years and restored to his previous position on William’s deathbed. He then went on to support the Norman Duke Robert Curthose’s rebellion against his brother William Rufus.

After the rebellion failed, Odo stayed in Bayeux and enlisted in the First Crusade. He died in Norman Sicily en route to Holy Land and is buried in Palermo’s Cathedral. Odo’s central role in the commission of the Tapestry and his life’s deeds provide us with the historical link that demonstrates the ascendence of the Normans upon the world stage. From the windswept channel of England to the sunny Mediterranean island of Sicily, the Normans had come along way since their marauding Viking roots. I highly recommend Palermo’s Monreale, it is an absolute must for anyone interested in Norman History. Both the Palermo Cathedral and Monreale are key sites containing the stories and remains of the other branch of the Norman ruling elite.