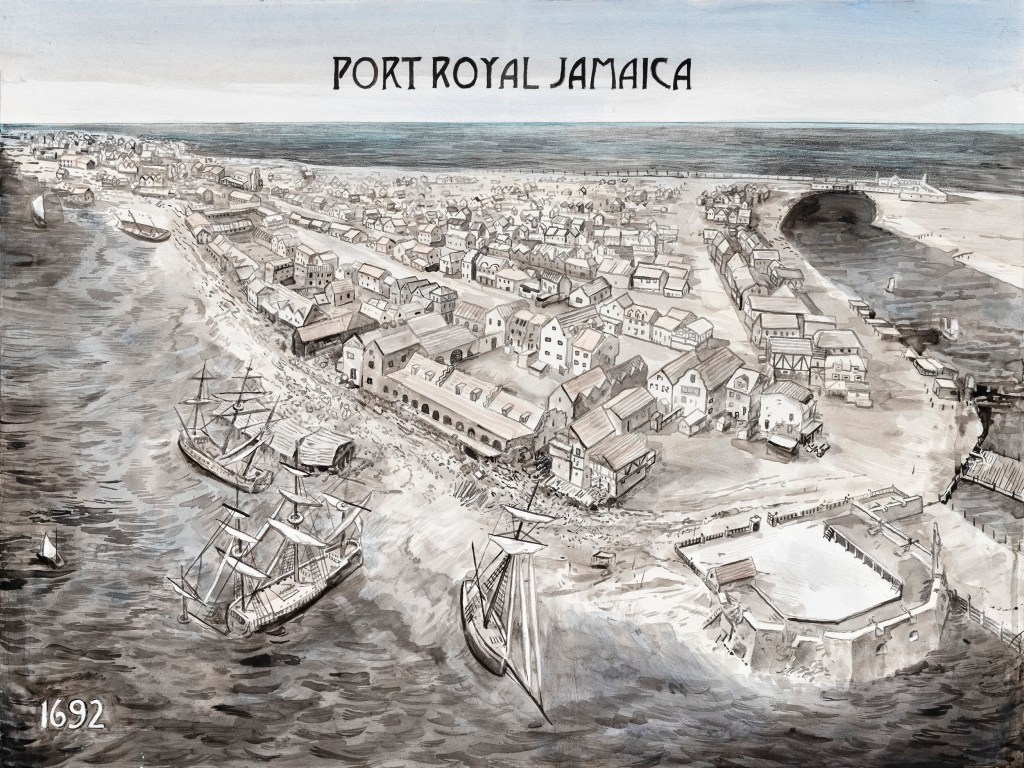

It’s June 7th and the year is 1692, the time is approaching noon at Port Royal, Jamaica, suddenly a massive earthquake turns the spit of sand into into liquid muck and an enormous tsunami sweeps away anything that hasn’t sunk below the surface waves already. This natural disaster destroys the major pirate haven of the West Indies, but will soon become a boon for another den of sin located off the coast of Madagascar.

The Island of Sainte-Marie located off the northeast coast of Madagascar, was perfectly placed along the spice routes of the British East India company and its syncretic ruling class of Malagasy Nobles and European Buccaneers had developed long tendrils reaching as far as the Hudson Valley. The first to discover the potential of the out of the way enclave by a former indentured servant by the name of Thomas Tew. He made his life as a privateer after serving out his penal sentence on Barbados or St. Kitts, his success brought him funds and crews necessary to attack French factories near the River Gambia. He set out in the year of 1692 and possessed letters of Marque that sanctified the venture from the governor of Bermuda. Extremely bad weather broke up this fleet and a vote was taken to cross the thin line between piracy and privateering. The voyage of his crew would come to represent what is described as the “Pirate Round,” ships would start in the Atlantic, move to the tip of Africa and either up the coast or onto India. The Island of Sainte-Marie was the perfect operating base from which to intercept trade between India and North America, while also positioning oneself to seize the Islamic trade in slaves and Haji pilgrims at the mouth of the Red Sea.

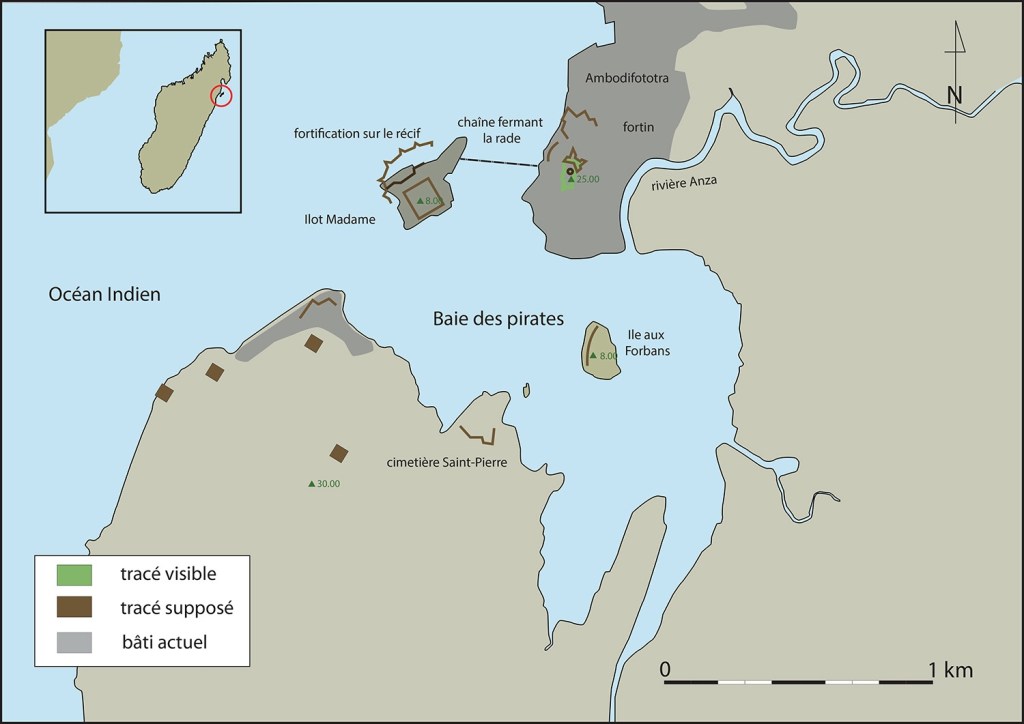

Two years before the disaster at Port Royal, a man by the name of Adam Baldridge was part of the crew of the slave ship “fortune,” whose trips produced a cheaper trade in bondage over the middle passage. Seeing the advantage of a beautiful landlocked bay, he elected to stay on the island of Sainte-Marie and set up shop. The bay he chose contained a protective sandbar at its mouth and was landlocked on three sides by elevated hills, these would aid in fortifications to protect the port. He quickly realized the value of his “neutral” stopover and ingrained himself amongst the local Malagasy nobility. He married several women of local notables and helped them pursue their wars on the mainland, this benefited Baldridge as the wars delivered large amounts of captured slaves.

As I’ve discussed in previous threads and on my podcast, the Dutch Merchant class was uniquely positioned to leverage their international contacts within the Navigation Act system. Poorly defined slave importation contracts for stock-sharing government backed companies, also placed Madagascar in a grey area. Early English governors of New York used privateers to take enemy prizes and of course do some trading while they happened to be sailing, but it was the NY Dutch merchants that provided the goods and funds for these privateers. The profits were great, a slave could be purchased for a few shillings in Sainte-Marie, as opposed to a few pounds in West Africa. There was plenty to split between the privateers, the New York politicians and the Patroons.

Greed tends to break up many a good criminal enterprise and this one was no different. Though the governors of New York issued the letters of marque and invested in the venture, men like Frederick Philispe decided to cut out the middle man. Privateers would pull into New York Harbor by night, but unload a significant amount of cargo onto schooners, this was sent up to the Patroon’s manor via the Hudson and small creeks. Eventually this scheme would be uncovered and the Patroon would find himself thrown off the executive council in 1698 for illegally conducting the slave trade in New York. Possibly more than 700 Malagasy slaves were smuggled into the plantation’s of the Hudson Valley, but the pirate haven declined by the first half of the 18th century, after suffering from British government interdiction and finally Mughal attacks.

One of the most intriguing mysteries is the role of Baldridge and his pardon, he seems to have cut a deal with British authorities and was never accused of piracy, though his actions clearly violated the Navigation acts and impeded on several national stock-charter companies. It is his correspondence that finally brings down Philispe and it seems like the British government’s way of getting back at an ungrateful partner, who they viewed had dishonorably cutout some very important men in New York.