Under The Green Harp and a Canal to Eire: The Battle of Ridgeway, 1866

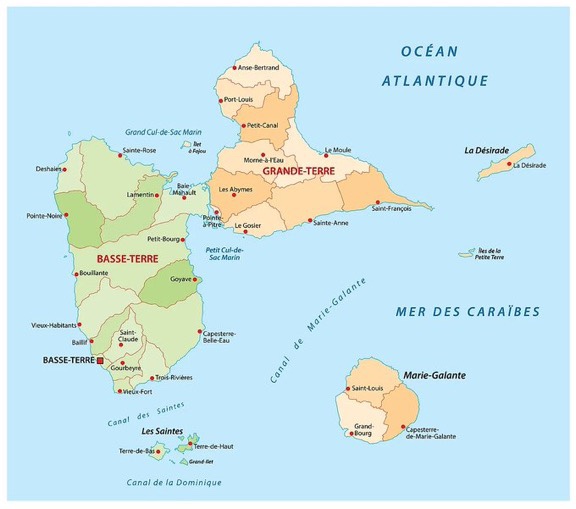

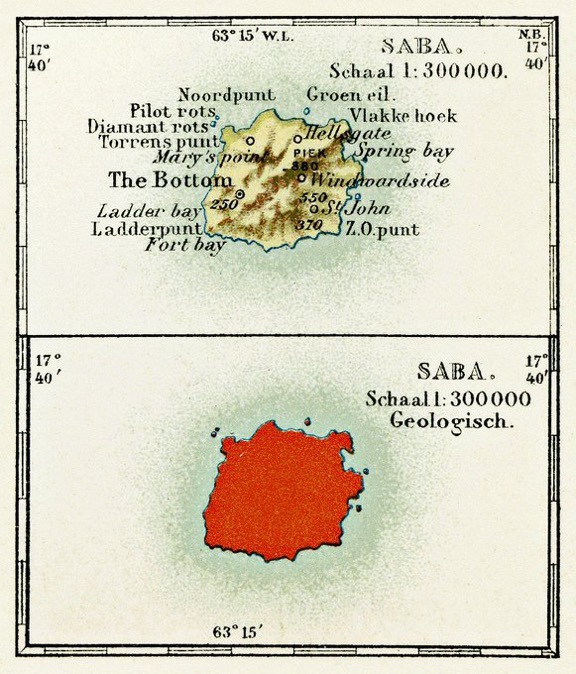

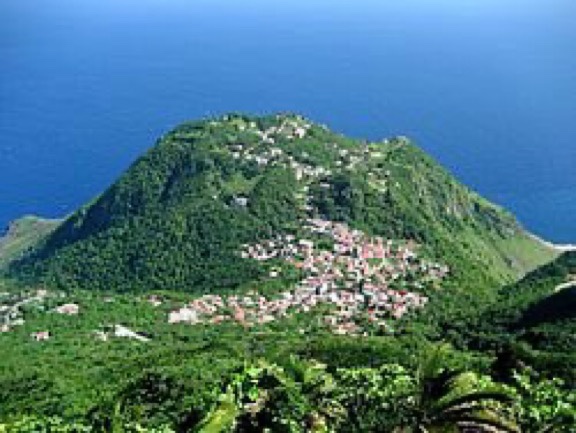

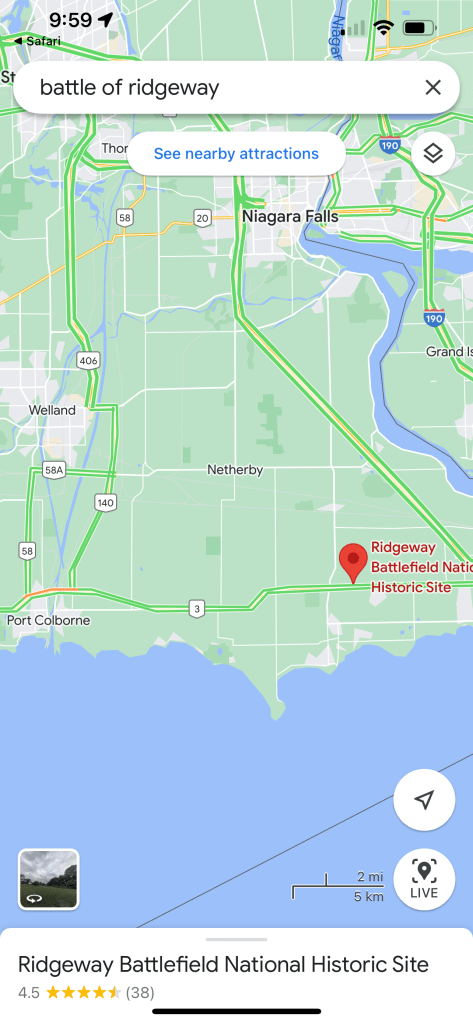

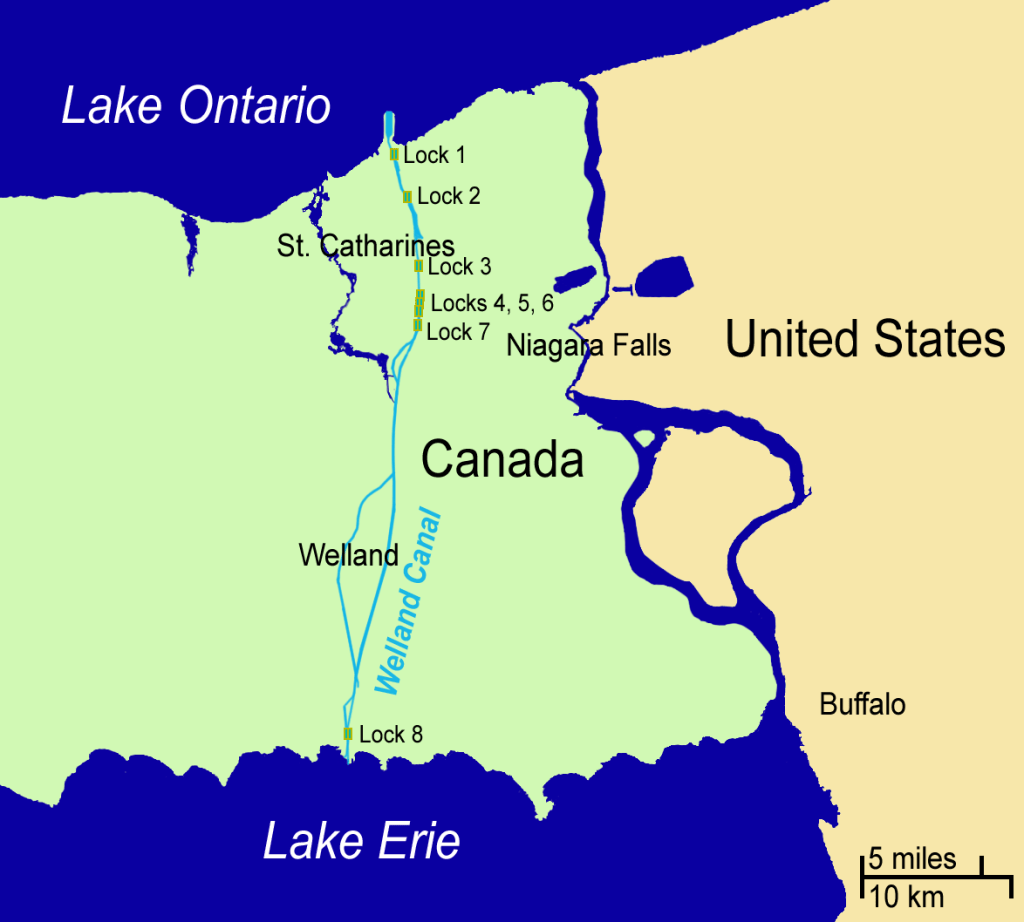

The Welland Canal is a crucial waterway in Ontario, that sits just west of Buffalo and occupies the Niagara escarpment. The canal connects Lake Ontario to Lake Erie and eliminated the need for a portage around the difficult falls. First constructed in 1824, it was enlarged and updated by mid century with a rail line that ran alongside. The Niagara River was the traditional defensive line for any invasion attempting passage between the lakes. American forces had made several successful attempts to ford the river at its southern terminus in The War of 1812. The completion of the canal now made this the new line against any possible American advance into Canada, but the Americans didn’t seem to be coming anytime soon. From 1860-1865, Canada’s neighbor to the south was involved in a brutal Civil War. It was in this conflict, where unseen future enemies gained crucial skills and insight into the bloody business of war.

Irish unemployment in New York City reached almost twenty-five percent by the start of the Civil War and they were hungry, pay offered by both the Union and Confederate forces was enticing. Over one million Irish had crossed the western ocean since the start of the “Great Hunger” in 1845, leaving behind over a million dead on the Emerald Isle. Abusive British Landlords, inept governmental responses, and eight hundred years of occupation had led to a Genocidal situation in Ireland and the resulting diaspora was seething with resentment. New York City was about one quarter Irish by the mid 1850s and these denizens packed into horrendous tenements on the Island of Manhattan. Faced with incredible discrimination by Protestant “No-Nothings,” the desperate population was fertile recruiting ground for resistance organizations against British rule in Ireland.

The great famine on the island had lead to rebellion in 1848, but this was quickly squashed. It’s leaders fled abroad and sought to reorganize their movement into an international organization seeking the independence of Ireland. In 1855, a former rebel by the name of John O’Mahony, helped found the Fenian Brotherhood and sought to use the masses of Irish immigrants in the US to further his cause. The US Civil War saw more than 220,000 Irish soldiers fighting on both sides. Recruits viewed their role as gaining experience for another struggle in which Ireland would be pitted against the British, while proving the bigoted Protestant public was wrong about their supposed lack of dedication to their new land. The Brotherhood was kept afloat by the hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants who bought bonds, these were assured to be made good six months after Ireland had been seized from the British. The Civil War had honed and hardened the Fenians by 1863, where in Chicago they launched a formal government in exile.

At war’s end in 1865, The Fenians expanded their government at a meeting in Philadelphia and turned their eye toward the application of military force. The brotherhood had organized a supply network centered on Buffalo, which was strategically located in upstate New York. The plethora of arms left over from the war and deep Fenian connections to army itself, allowed the organization to properly stock supply depots aimed at dismantling British rule in Canada. They were able to obtain over 4,000 muzzle loading rifles through auction and US government programs that allowed Union veterans to buy their arms kit. Fenian goals were to seize and hold British transportation networks in Canada, these gains would be exchanged for Ireland’s freedom.

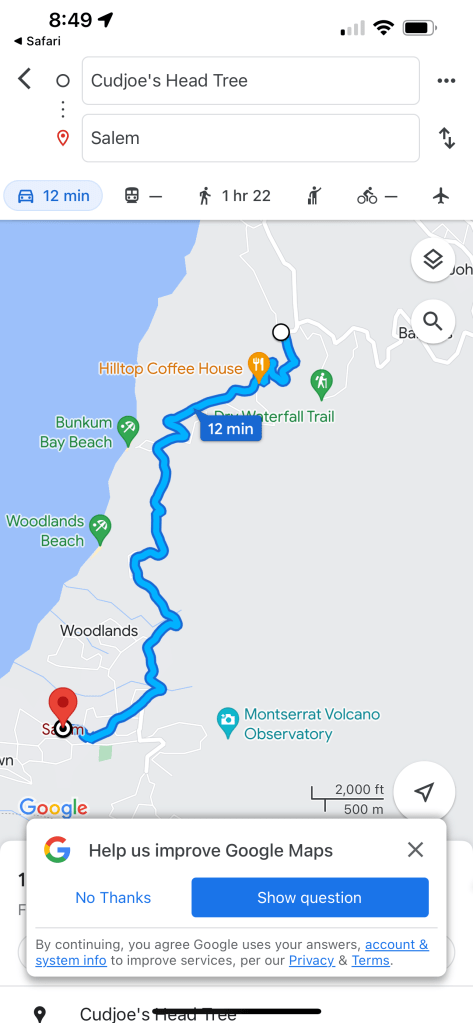

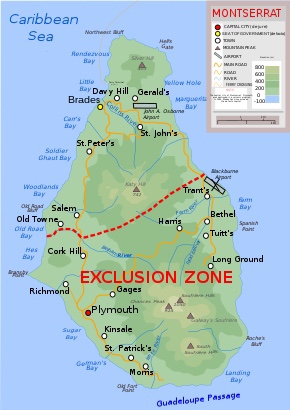

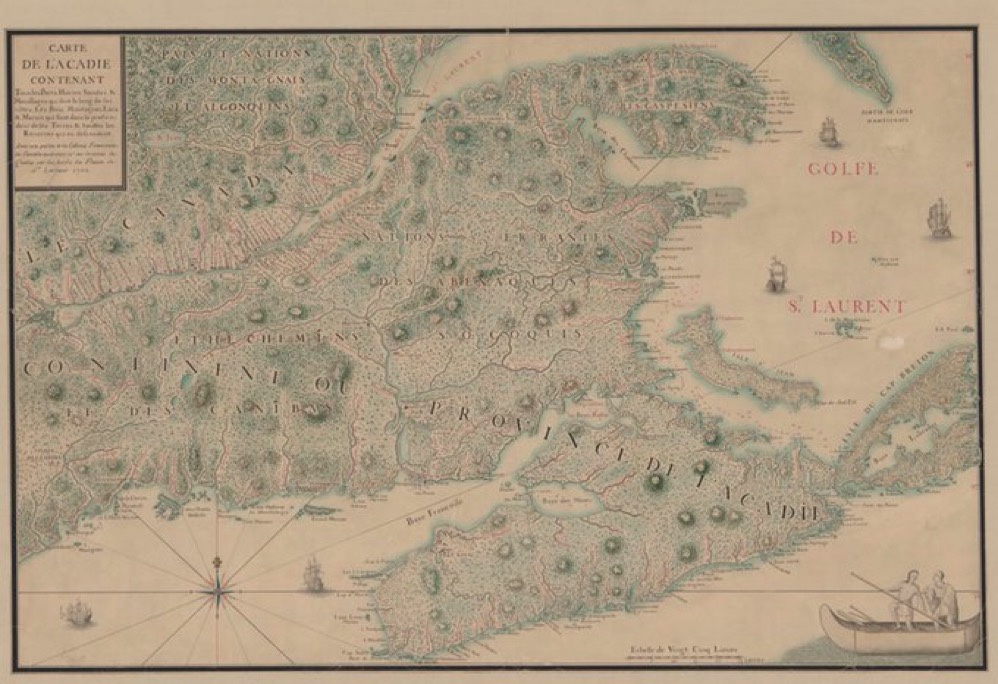

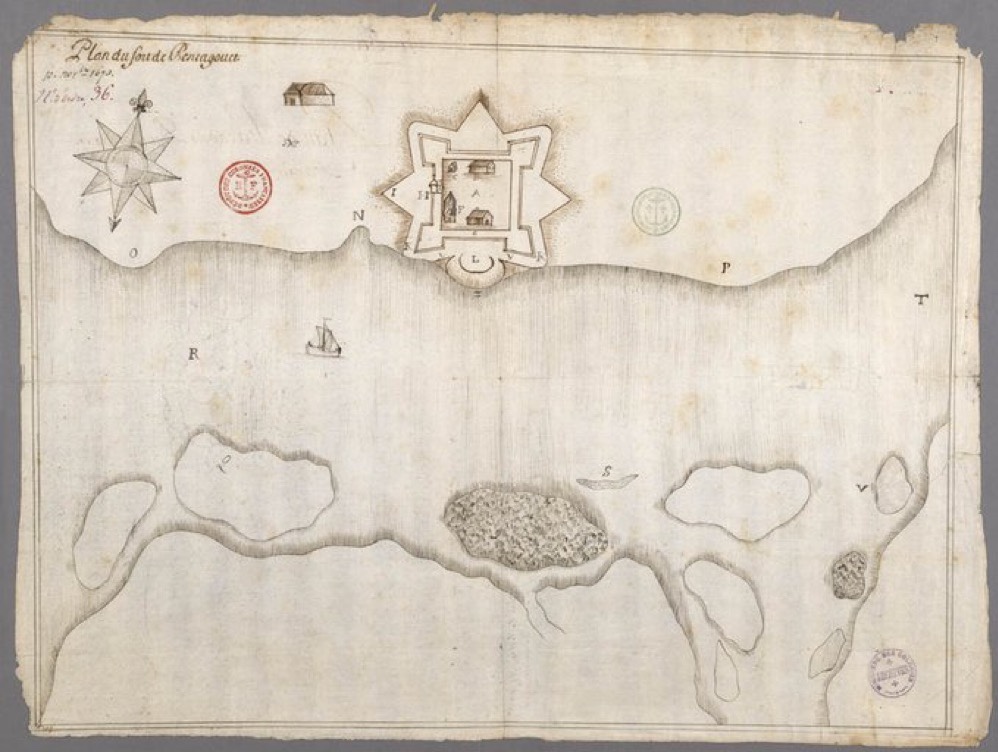

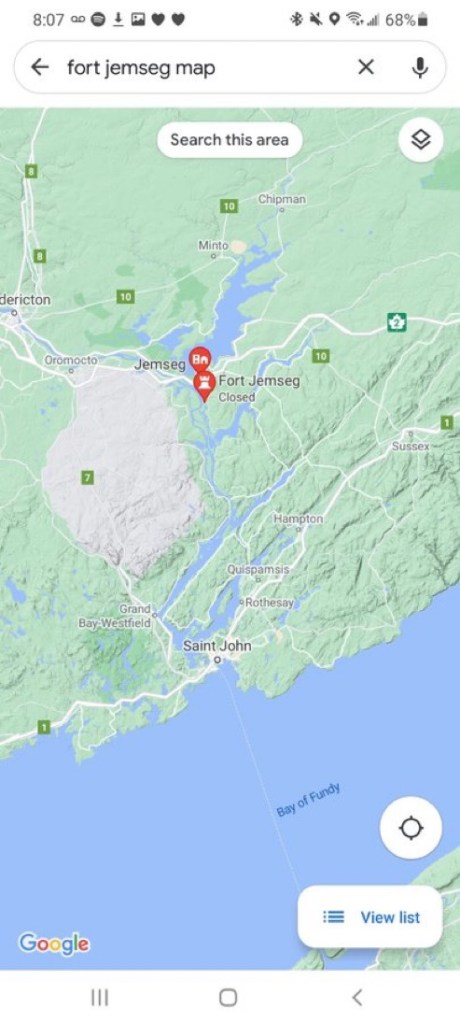

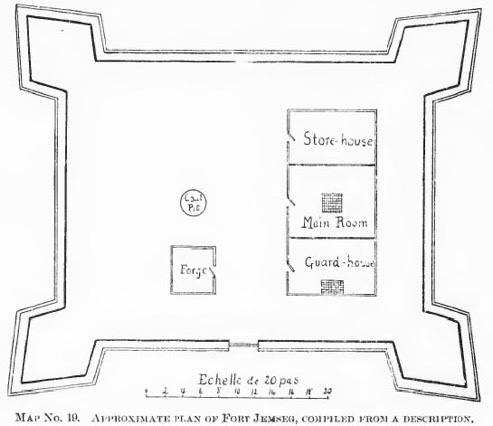

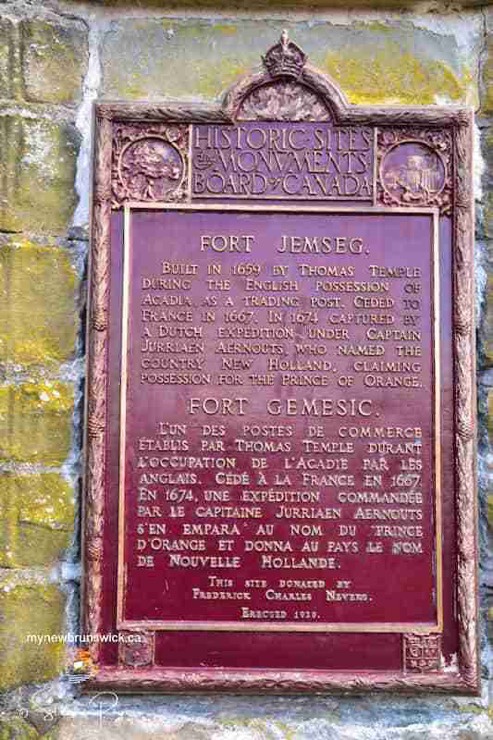

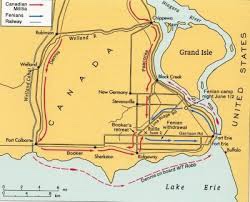

An early raid on April of 1866 against British Campobello Island failed, the Fenians had hoped to hold the island and disrupt shipping into the Bay of Fundy. An attack into Canada’s heartland from multiple directions had initially been planned, with Fenian operatives establishing spy networks north of the border and the 250,000 Irish-Canadians being seen as likely sympathizers. After the earlier failed campaign off the coast of Maine, Brotherhood support was faltering. The shadow government in exile had to use its resources now, or lose them to complacency. By May 1866, multiple groups of Fenians were mobilized and called to positions to across the Upper Great Lakes. Supply and logistic issues narrowed down the launch pad to Buffalo, New York. This big trading entrepôt on the international border had a large Irish population and transportation networks that could hide Fenian supplies. The US government at this point was agnostic, given British support for the Confederacy during the war and cross-border raiding from Canada. Fenian attempts to organize their attacks were helped by the fact that Canadian forces were worn out from earlier alarms of cross-border invasions supposedly targeting the Niagara area.

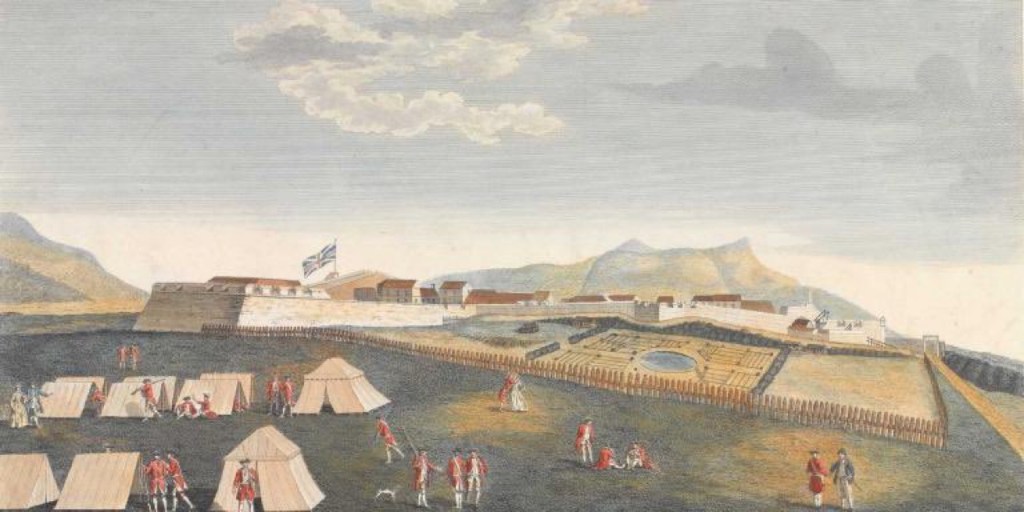

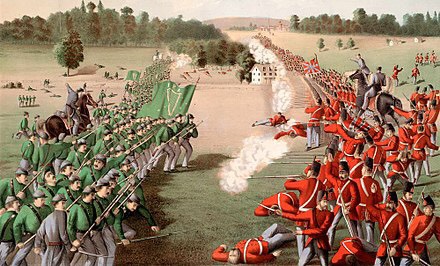

The gathering Fenian force didn’t go unnoticed, as Canadian spies and even Buffalo’s Mayor had sent alerts to British officials. An odd mixture of old Confederate and Union uniforms clad a united Irish body of patriots, as they looked out upon the Niagara River on the night of May 31st. As more than eight hundred Fenians found boats and crossed in the early morning hours of June 1st, the US gunboat that normally patrolled the area had been disabled temporarily by Fenian agents. Canadian militia were awoken during the middle of the night, including the Queen’s Own Rifles and the University Rifles of Toronto. These forces took ships across across Lake Ontario and made their way toward the southern terminus of the Welland Canal. By midafternoon on the 1st, professional British forces mobilized out of Hamilton and made their way by train toward the Niagara peninsula.

The Fenian army immediately set out for old Fort Erie, pulling up railroads tracks and cutting telegraph wires. Occupying the Village of Fort Erie, Fenian leaders read out a proclamation to the people of Canada that sought to clarify their war aims.

To the people of British America:

We come among you as foes of British rule in Ireland. We have taken up the sword to strike down the oppressors’ rod, to deliver Ireland from the tyrant, the despoiler, the robber. We have registered our oaths upon the altar of our country in the full view of heaven and sent out our vows to the throne of Him who inspired them. Then, looking about us for an enemy, we find him here, here in your midst, where he is most vulnerable and convenient to our strength. . . . We have no issue with the people of these Provinces, and wish to have none but the most friendly relations.

Our weapons are for the oppressors of Ireland. our bows shall be directed only against the power of England; her privileges alone shall we invade, not yours. We do not propose to divest you of a solitary right you now enjoy. . . .

The Canadian forces were now in two columns, one to the west at the southern terminus of the canal and one to the north coming from Hamilton. In addition, the US Navy had fixed its patrol ship and now cutoff supplies across the Niagara by days end, on June 1st. The Fenians were outnumbered by at least 5-1, with their only hope being to separately intercept and destroy the two columns piecemeal. The Irish choose to march north along the river and then west, in hopes of meeting one of the columns before they could combine. The column coming from the north consisted of professional and well armed British soldiers, but the column from the west were made up of mostly untrained militia.

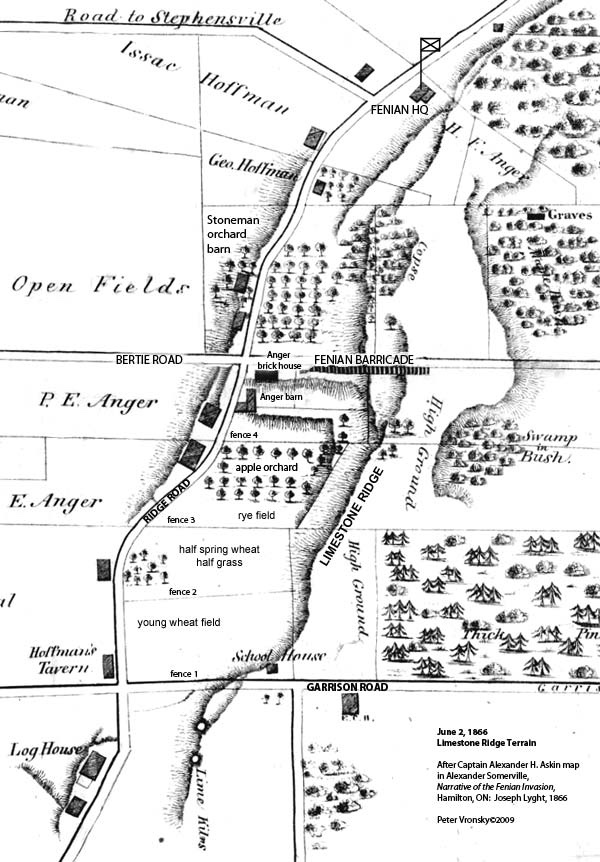

This western column arrived in the Canadian village of Ridgeway by the morning of June 2nd, while several miles north, the Fenians had seized some heights alerted to them by spy networks. This position placed the Fenian forces between the two British columns to prevent their attempted consolidation. The Fenian’s constructed a breastwork along the ridge that blocked the route and waited for the untrained Canadians to attempt their assault. Being crack Civil War Veterans, the Fenians calmly poured fire upon the oncoming green Canadian Militia. Canadian skirmishers had little ammunition, but pressed forward despite the onslaught. Being outnumbered and in risk of being flanked, the veteran Irish soldiers performed a feint. They retreated in good form and the inexperienced Canadians took the bait. In the wild frenzy to chase down the Irish, the center of the Canadian line became overextended, it was now that the Fenians wheeled and unleashed a bayonet charge. In the confusion unleashed by the charge, Canadian officers called their men into a Calvary square by mistake. Now stationery, The Fenians were provided with perfect targets for their seasoned veterans. After two brutal hours of fighting, the British retreated and the Fenians seized the flag of Queen’s Own Rifles.

The victory quickly circulated like wildfire on each side of the border and the Irish gave up their pursuit of the retreating British. Hundreds of Fenian reinforcement volunteers from across the US, suddenly started to make their way toward the arena of battle, but there was another column of more professional soldiers still out in the field. The Fenians decided to return to Fort Erie, so they could be resupplied from the US side of the border. Canadian residents of village of Fort Erie, engaged the returning Fenians, as they had repossessed the old fort when the Irish had marched off to Ridgeway. A running battle was fought throughout the village and a large crowd gathered to watch from the Buffalo side. Having pushed the small Canadian force out of the village, Fenian forces now thought they controlled their supply route.

The US Navy had completely shutdown the Niagara River and no other reinforcements were piled be arriving though. The next morning, The Irish were forced to recross the Niagara to Buffalo, but they had freed their Canadian prisoners beforehand. The US government forced the surrender of the Irish force and imprisoned them upon US soil. While the officers were given comfortable quarters, the rank and file were still kept abroad US naval ships near Buffalo. US Army units under the command of General Meade, now kept careful watch over the borders, from New York to Vermont. The Fenians rank and file were released after three days, but the officers faced violations of US neutrality laws. Several days later, 1,000 Fenian recruits marched over the border from Vermont and occupied several small towns. This force was confronted by a much larger Canadian one and retreated back across the border in disgrace.

The Fenian raids came at a delicate time in the development of a Canadian national identity. Some saw a Confederation as the only true way to protect against further raids from the south, while others used the raids to argue for direct British rule to continue. The Battle of Ridgeway marks the end of the long and fractious border conflicts occurring between New York and Quebec, it’s an addendum to the Podcast which will be covered in the final season.